Richard Hodges recently asked me to compose a song based on the Epic of Gilgamesh. This piece is the result.

It’s the first in what will be a series of songs based on the story of Gilgamesh. The project is ongoing.

The original lyrics were generated by Richard using AI. They were workmanlike enough for what they were, but I ultimately made major changes during the creative process, so what follows can hardly be described as a product of AI.

While AI sometimes enjoys various advantages as a tool, I won’t be using it for the remainder of the lyrics in this series.

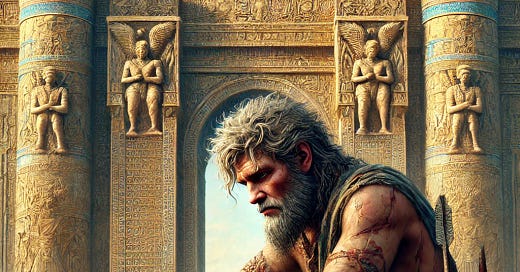

The image of Gilgamesh accompanying this post is, however, generated by Dall-e, which can be a terrific tool at times.

So… why Gilgamesh?

There’s little argument on this matter: it’s primary. Epics in the western world begin centered around this one. Scholars agree that the Illiad and the Odyssey drew parts of their form and substance from this ancient epic; and the bardic tradition that birthed it is still alive in some of the remote parts of the world today, despite the relentless efforts of modernity to destroy almost everything real which remains from traditional societies that understood matters of the heart and not just the head.

Gurdjieff reported that his father recited the epic of Gilgamesh to him when he was a child; and it’s well known to anthropologists, if no one else, that these epic traditions in bardic poetry, recited or sung from memory by individuals who are trained in these extraordinary feats of recollection, have been able to preserve such texts essentially unchanged over many generations and pass them on through time as mythical memories of man.

Yet they are more than mythical memories; the intention with such tales is always to have them take up residence in the subconscious, where– as Gurdjieff pointed out– that most very precious resource, conscience, is still alive in man.

So they serve a special purpose.

When Gurdjieff saw, after several decades of teaching in the way that he did with P. D. Ouspensky, that the ”technology-based” approach to inner work was a failure—and we can presume that this is exactly why he conducted his ”experiments“ on people in the first place, to see if it actually ”worked” —it didn’t—he reverted to a completely new form of inner work, stripped of all the “information and technology” he had imparted in the early years of his work.

He replaced the entire structure with a grand and impossible myth.

In this sense, Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson owes its existence itself to Mr. Gurdjieff's father and his recitation of the epic of Gilgamesh; because Beelzebub’s Tales is a new epic of Gilgamesh for a modern age. Myths, by the way, must be impossible: that’s what grants them their power. They defy rational assumptions, which are the original source of our spiritual malaise in the first place.

The epic of Gilgamesh has been mistaken by archaeologists for an embroidered version of events that actually occurred in the external world; yet though there is probably a grain of truth there, it’s much more than that. It's a deep psychological allegory – and it is more than just psychological, it is a spiritual allegory about the condition of mankind: our separation from our essence, a descent into inner tyranny, which looks to us like an ascent, and the struggle to rediscover the essence, form a partnership with it—in the process, inevitably, we corrupt it the moment we touch it with the crafty priestess meant to allure it back to us — and remake ourselves in order to defeat the creatures of evil we’ve become. The consequent trauma as the essence in this particular tragedy dies forces us to examine our gravely mistaken assumptions about ourselves, and the nature of life and being.

That’s indeed a mouthful; but myths, although they come out of our mouths, are made to fill not just mouths and make tongues wag, but to fill bellies: to feed the marrow of the bones, and to re-infuse the heart with the miraculous, which it has forgotten in its pursuit of sex, power, money, and all the other trappings of a material kingdom.

Gurdjieff’s intention was for Beelzebub’s Tales to serve just such a purpose; it is in fact, a bardic vehicle. The word bard itself indicates a mode of transportation, coming as it does in a transferred sense from barde, "armor for the breast and flanks of a war horse,” which in turn owes its origin to the Arabic barda’a, which means saddlecloth or padded saddle.

Bardic vehicles are, in other words, that with which we prepare ourselves to ride our horse; and of course, the horse represents the feelings in allegories of the soul.

So if we wish to come into a new contact with feeling, we look to the bard, not the scientist.

When I was writing the music for some of the tales presented in Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, I did so specifically because setting Gurdjieff's words to music was not just a challenge, but a way of making them come alive in a completely different manner. This seems necessary, because we have to help mythology to live in us as a force, not view it from the outside as a phenomenon. We have to inhabit it, not study it; and so much of what is discussed about Beelzebub’s Tales these days is study, not inhabitation.

A revolution is called for.

Writing the music for the story of Gilgamesh, in other words, has involved me in a new form of immersion into this ancient tale; and in the process, I’ve been forced to re-examine the tale itself from a completely new point of view, as though it were a living thing meant to be resident within the heart and the soul. To snatch it from the realm of dusty clay tablets and archaeology, which it has been resident in for the several centuries since its re-discovery, and bring it back into the world of the living in such a way that it can relate to our contemporary sensibilities.

King Gilgamesh Lament—lyrics Verse 1 I am Gilgamesh the mighty Hear my name I am Gilgamesh the mighty My fathers came From the ancient city of Uruk Where I earned my fame. My strength unmatched, my courage bold, A story known since days of old I am Gilgamesh the mighty, Hear my name Chorus I am King Gilgamesh the mighty, Destroyer of my enemies With Enkidu by my side, we face the night, Together we conquer, in the eternal fight. Verse 2 Across wild lands, our footsteps roar. , We defeat monstrous entities while dressed in shorts In search of glory and legends' lore We fought the bull of heaven and so many more We kicked the asses of Gods of power Did it all in an hour Chorus I am King Gilgamesh the mighty, Destroyer of my enemies With Enkidu by my side, we face the night, Together we conquer, in the eternal fight. Verse 3 In the depths of grief, when my brother fell, I sought the secret of life's eternal spell. Through the dark and distant, to the ends of time, I saw that truth was never mine. I am King Gilgamesh, Hear my name I am King Gilgamesh Hear my name I felled sacred trees and made a throne Challenged the underworld for everything unknown Now I know that death is certain and everything will fail, Even though I’ve conquered heaven Held its serpent by the tail I am King Gilgamesh Hear my name

all music, lyrics and artwork copyright 2024 by Lee van Laer. No use or reproduction without express permission of the author.

warmly,

Lee

Share this post